History

The Rise And Fall Of Anini ,The Taxi Driver Turn Armed Robber

History

Late Prof. Haruna Wakili: A Legacy of Scholarship, Service, and Integrity

By Dr. Yau Muhammad

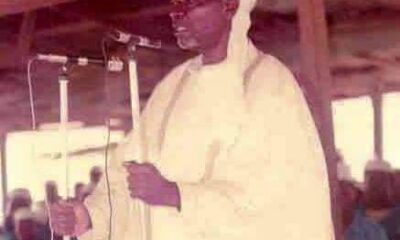

Professor Haruna Wakili (1960–2020) was a distinguished Nigerian academic, historian, and public servant whose contributions to education and governance left an indelible mark on both Bayero University, Kano (BUK), and Jigawa State.

Early Life and Academic Pursuits

Born in June 1960 in Rumfa word, Hadejia, Jigawa State, Prof. Wakili began his educational journey at Government Teachers College, Dutse, obtaining his Grade II Certificate in 1980. He proceeded to Bayero University, Kano, where he earned a B.A. in History in 1985, graduating as the best student in his department and receiving the Prof. M.A. Al-Hajj Memorial Prize and the Prof. Michael Crowder Prize for excellence in modern African history. He further obtained an M.A. in History in 1989 and a Ph.D. in 1998 from the same institution. In 2004, he expanded his academic horizons by earning a certificate in American History from New York University, USA .

Academic and Administrative Roles at Bayero University

Prof. Wakili commenced his academic career at BUK in 1990 as an Assistant Lecturer in the Department of History. Over the years, he rose through the ranks, becoming a Professor and Head of the Department. He was notably the only individual to serve twice as Director of the Aminu Kano Centre for Democratic Research and Training (Mambayya House), where he spearheaded significant research initiatives and promoted democratic studies . In 2018, he was appointed Deputy Vice Chancellor (Administration), a role he held until his passing in 2020 .

Commissioner for Education in Jigawa State

Between 2010 and 2015, Prof. Wakili served as the Commissioner for Education, Science, and Technology in Jigawa State under Governor Sule Lamido’s administration. During his tenure, he was instrumental in transforming the state’s educational landscape. His notable achievements include the establishment of Sule Lamido University in Kafin-Hausa, aimed at expanding higher education access for the state’s residents . He also oversaw the construction and renovation of schools, enhancement of teacher welfare, and implementation of training programs to improve educational standards .

Scholarly Contributions and Mentorship

An accomplished historian, Prof. Wakili specialized in the study of riots, revolts, conflicts, and peace studies in Nigeria. His doctoral thesis focused on the phenomenon of riots and revolts in Kano. He authored several publications, including “Turawa A Kasar Hadejia: Karon Hadejiyawa da Turawan Mulkin Mallaka” and “Religious Pluralism and Conflict in North Western Nigeria, 1970–2000” . Known for his intellectual rigor and integrity, he emphasized original research and was a staunch advocate against plagiarism. His mentorship inspired many students to pursue academic excellence and critical thinking .

Legacy and Tributes

Prof. Wakili passed away on June 20, 2020, at the National Hospital in Abuja after a prolonged illness. His death was deeply mourned across academic and political communities. BUK’s Vice Chancellor, Prof. Muhammad Yahuza Bello, lauded him as a dedicated scholar and administrator . Former Governor Sule Lamido described him as an epitome of humility and selfless service . The Emir of Hadejia, Alhaji Adamu Abubakar Maje, remembered him as a close confidant and a man devoted to humanity .

Prof. Haruna Wakili’s life was characterized by unwavering commitment to education, scholarly excellence, and public service. His contributions continue to inspire and shape the academic and educational landscapes in Nigeria.

Allah ya jikan Mallam da rahama. Ameen thumma Ameen.

Wassalam

History

History, Identity, and the Unexpected Echoes of Ancestry”-Dokaji

By Huzaifa Dokaji

About 2 years ago, a good friend of mine who works and lives in the UK engaged me in a conversation about the history of Northern Nigeria. The discussion moved from topic to topic until we ventured to the Sokoto Jihad. After several exchanges, we agreed to create a Clubhouse room to discuss texts written by the Sokoto Jihadists. One of the most fascinating conversations we had focused on the intellectual exchange between Sokoto and Borno, or more precisely, between Sultan Bello and al-Kanemi. Like my friend, I found much of al-Kanemi’s reasoning compelling, except his argument that people should only preach against social and political corruption. To me, that view felt overly idealistic and did not align with the broader Islamic impetus.

My friend grew increasingly critical and more interested in the subject. The engineer in him wanted to understand how, to borrow from Prof. Samaila Suleiman Yandaki, the Sokoto history machine produced and disseminated its narratives of rebellion and legitimacy. We agreed and disagreed, but always in pursuit of the truth, elusive and debatable as it was. That was possible perhaps because neither of us was blinded by ethnic fetishism.

I must add that when all those conversations were going on, my friend felt his connection to that history was merely a result of geography and faith. He often tried to discuss it as a detached observer, carefully framing his questions to me as someone he considered a legacy of the very history we were scrutinizing.

Not long ago, my friend reached out with what was definitely an exciting and shocking news to him. He had taken one of those ancestry DNA tests, and the result showed he was Fulani. Through the company’s database, he identified and reconnected with a relative. Since they were both in the UK, they met and had a fruitful discussion, and to my friend’s astonishment his paternal descent goes back directly to Abdullahi b. Fodio.

This discovery, while exhilarating for him, also unsettled the very framework through which he had previously engaged with history. It blurred the line between the observer and the subject, raising questions about belonging, identity, and the burden of historical legacy. A realization hit him that in this part of the world, ethnicity is never just about bloodlines or surnames; it is a contested space shaped by memory, politics, and perception. My friend’s new discovery did not simply anchor him to a lineage; it dragged him into a narrative that is still very much alive, one that shapes contemporary anxieties, resentments, and aspirations.

His realization took us back into a discussion we had on Club House on the dangers of simplistic historical, or more correctly, political narratives. As we debated at the time, I argued that the past was never the neat category some would have us believe. The story of Ali Aisami makes this clear. Permit me to digress a little.

Ali Aisama was a Kanuri man who was forced to flee his town after it fell to the Jihadists. After his parents died, and he married his surviving sister off to his father’s friend, he sought refuge with another family friend in a Shuwa Arab town. One night, while returning from a nearby town, he was kidnapped by Fulani slavers. The following day, they sold him to Hausa slavers in Ngololo market, about 55 miles from the town of Shagou.

The Hausa slavers fettered him and marched him for 22 days to Tsangaya, a village southeast of Kano and known at the time for its dates. From there, he was moved to Katsina and later to Yawuri, where he was sold to the Borgawa. His new Borgu master took him home, and put iron fetters on him day and night until he finally sold him to a Katunga (Yoruba) king/prince in old Oyo.

The king/prince mistook Ali Aisami’s tribal marks for royal ones (since they look like Yoruba royal marks), and treated him honorably. However, after the jihad broke out in Ilorin, out of fear that Ali Aisami might join his Muslim brethren, he was taken to Dahomey and sold to European slave dealers. Eventually, he was freed by British anti-slavers and resettled in Sierra Leone, where he converted to Christianity and adopted the name William Harding.

Ali Aisami’s journey across ethnic, political, and religious boundaries show that 19th-century Northern Nigeria was more complicated than comtemporary narratives suggest. His story, like many others, disrupts the simplistic binaries that often dominate discussions of the 19th century—binaries that cast certain groups primarily as victims and others as aggressors or perpetrators. In reality, such roles were fluid, reversible, and deeply embedded in broader social institutions, particularly slavery. Although Ali Aisami was Kanuri, a group that were said to enslave Hausa and other less powerful groups, Aisami himself was enslaved by Fulani captors, sold to Hausa slave traders, and passed through a complex chain of transactions that involved the Borgawa, Yoruba royalty, and eventually European slave dealers.

More surpringsly, the Borgawa and the Hausa (recently framed as “helpless” victims in the midst of Kanuri and especially Fulani imperialists) were at different moments and in different contexts, complicit in the same systems of exploitation. Narratives like Ali Aisami’s compel us to rethink ethnic identity not as a fixed or moral category but as one embedded in larger structures of power, commerce, and survival.

Furthermore, they also reveal how the legacy of the Sokoto Caliphate cannot be read solely through the lens of ideological or religious transformation, but must also be situated within the material realities of slavery, warfare, and shifting political alliances. In this sense, Aisami’s life not only humanizes the abstract forces of the 19th century. It reminds us that historical agency often operated within morally ambiguous frameworks, where perpetrators and victims could inhabit the same position at different moments.

My point here is it is not intellectually helpful to see the jihad starkly as a war between right and wrong (as its protagonists do) nor dryly as the victimization of a certain group (as its antagonists do). Rather, it is more productive to approach 19th-century Northern Nigeria as a site of competing visions, shifting alliances, and intersecting hierarchies, in which individuals and groups navigated complex moral, economic, and spiritual terrains. This requires moving beyond essentialist readings that reduces history into tidy moral tales or ethnic scorecards. It calls for a method attentive to contradiction, nuance, and context. Only such an approach allows us to hold multiple interpretations at once: that perhaps, the jihad did led to religious and intellectual reform, and at the same time brought about new systems of enslavement and exclusion.

It is this methodological caution, grounded in a critical reading of sources and a suspicion of inherited and currently promoted narratives, that enables a fuller, more honest reckoning with the past. Here, the past is treated not as gold or garbage, but as a tangled emblem of value and ruin.

Anyways, the end of the gist is that after a Fulani Professor here in the US told me his ancestry DNA revealed strong Yoruba ties, I decided to send mine in to know where I fit. Who knows what I will turn out to be. I mean, it might not be a coincidence that I was almost born in Lagos and somehow vibe effortlessly with Yoruba people. Maybe it’s in the blood, or maybe, it’s just being Professor Aderinto’s mentee, I developed a soft spot for amala and fuji music. We will know in few months.

Huzaifa Dokaji wrote from the United States of America

History

Today in History: Former Senate President Chuba Okadigbo Was Gassed To Death

By Abbas Yushau Yusuf

On September 23, 2003, the vice-presidential candidate of the All Nigeria Peoples Party, Chief William Wilberforce Chuba Okadigbo, was allegedly gassed at Kano Pillars Stadium by security agents during a rally of the defunct All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP), led by the opposition candidate in the 2003 general elections, General Muhammadu Buhari (retired).

The ANPP and its candidate, Muhammadu Buhari, staged the opposition rally at Sani Abacha Stadium as a prelude to their court case at the Presidential Election Tribunal in Abuja, led by Justice Umaru Abdullahi.

The rally, which had thousands of Buhari’s supporters in attendance, was graced by the new Governor of Kano State, Malam Ibrahim Shekarau, his late Deputy, Engineer Magaji Abdullahi, Hajiya Najaatu Muhammad, and John Nwodo Junior.

The ANPP National Chairman, Chief Donald Etiebet, also attended the rally. However, apart from Malam Ibrahim Shekarau, the rest of the ANPP Governors were not in attendance, including Ahmad Sani Yerima of Zamfara, Adamu Aliero of Kebbi, the late Bukar Abba Ibrahim of Yobe, Senator Ali Modu Sheriff of Borno, and Attahiru Dalhatu Bafarawa of Sokoto.

Aware of Dr. Chuba Okadigbo’s health condition, the then Federal Government under Chief Olusegun Obasanjo did not want the rally to proceed. Security personnel mounted the entrance to Kano Pillars Stadium to prevent entry into the field until the Kano Governor, Malam Ibrahim Shekarau, ordered the youth to break the gate, allowing the opposition figures to enter.

Upon entering the stadium, Malam Ibrahim Shekarau chastised his predecessor and the then Minister of Defence, Engineer Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso, for not visiting Kano since handing over power on May 29, 2003. He referred to Kwankwaso as “Ministan tsoro,” meaning “Minister of Fear.”

On returning to Abuja, the late William Wilberforce Chuba Okadigbo died on Friday, September 25, 2003, following the alleged gassing by security agents at Kano Pillars Stadium.

Dr. Chuba Okadigbo was the political adviser to former President Shehu Shagari during the Second Republic. He hailed from Oyi Local Government in Anambra State.

-

Opinion4 years ago

Opinion4 years agoOn The Kano Flyovers And Public Perception

-

Features5 years ago

Features5 years agoHow I Became A Multimillionaire In Nigeria – Hadiza Gabon

-

Opinion5 years ago

Opinion5 years agoKano As future Headquarters Of Poverty In Nigeria

-

History5 years ago

History5 years agoSheikh Adam Abdullahi Al-Ilory (1917-1992):Nigeria’s Islamic Scholar Who Wrote Over 100 Books And Journals

-

Opinion4 years ago

Opinion4 years agoMy First Encounter with Nasiru Gawuna, the Humble Deputy Governor

-

History5 years ago

History5 years agoThe Origin Of “Mammy Market” In Army Barracks (Mammy Ochefu)

-

History4 years ago

History4 years agoThe History Of Borno State Governor Professor Babagana Umara Zulum

-

News4 years ago

News4 years agoFederal University Of Technology Babura To Commence Academic Activities September